Does Reading Reduce Cognitive Decline?

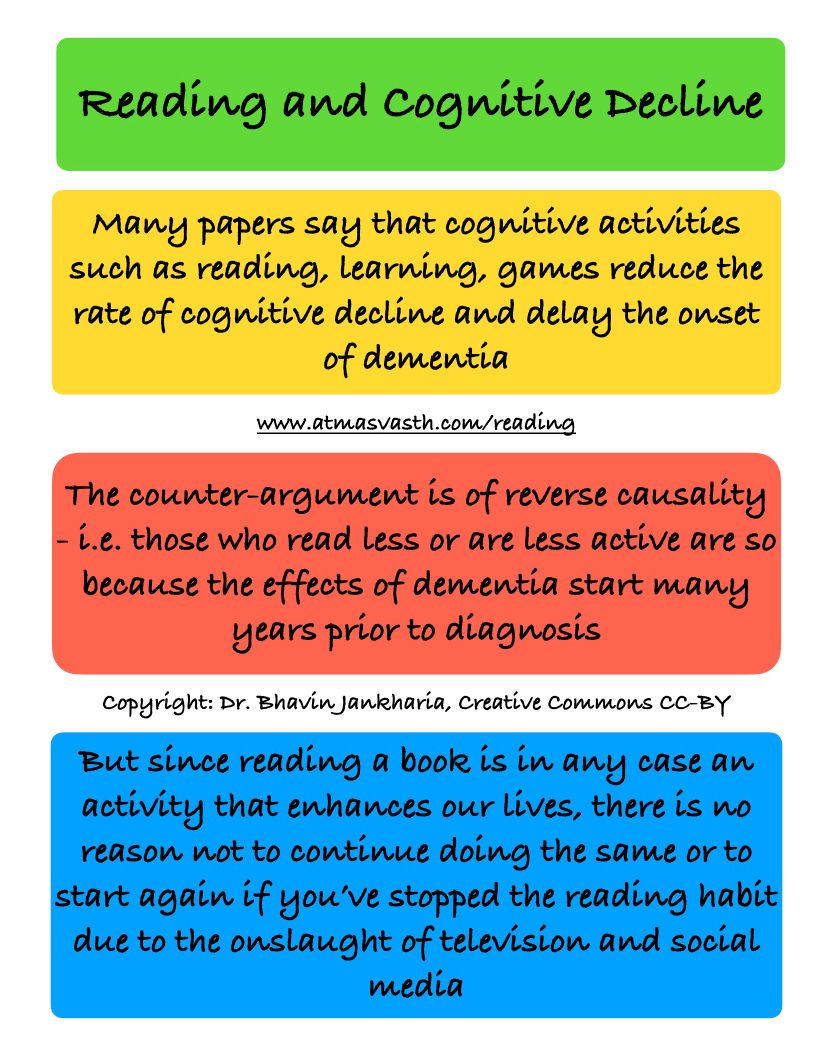

Reading as a cognitive activity builds cognitive reserve and helps reduce the rate of cognitive decline and/or delay the onset of dementia

The last time I wrote about cognitive decline, I introduced the term “cognitive reserve” and quoted,

“Individuals with increased cognitive reserve tend to be more highly educated, possess higher IQs, reach higher occupational attainment, and are involved in a diverse range of leisurely activities.” [1].

One question that keeps coming up is whether therefore as we age, apart from physical activity, do we need to keep the brain engaged and does that help reduce the rate of cognitive decline. This is what I wrote at the end of the same article that was based on the Nun study [2].

“Even if your brain is affected by pathologic processes that cause dementia and cognitive loss, a high level of education coupled with life-long learning will allow you to build significant cognitive reserve to help prevent the occurrence of clinical dementia and/or reduce the amount of significant cognitive loss if it does occur. Irrespective of your education level, it is a good idea therefore to start structured learning and to cultivate a wide range of leisure activities and hobbies that involve reading and learning and then try and implement that knowledge gained, in the best possible way.”

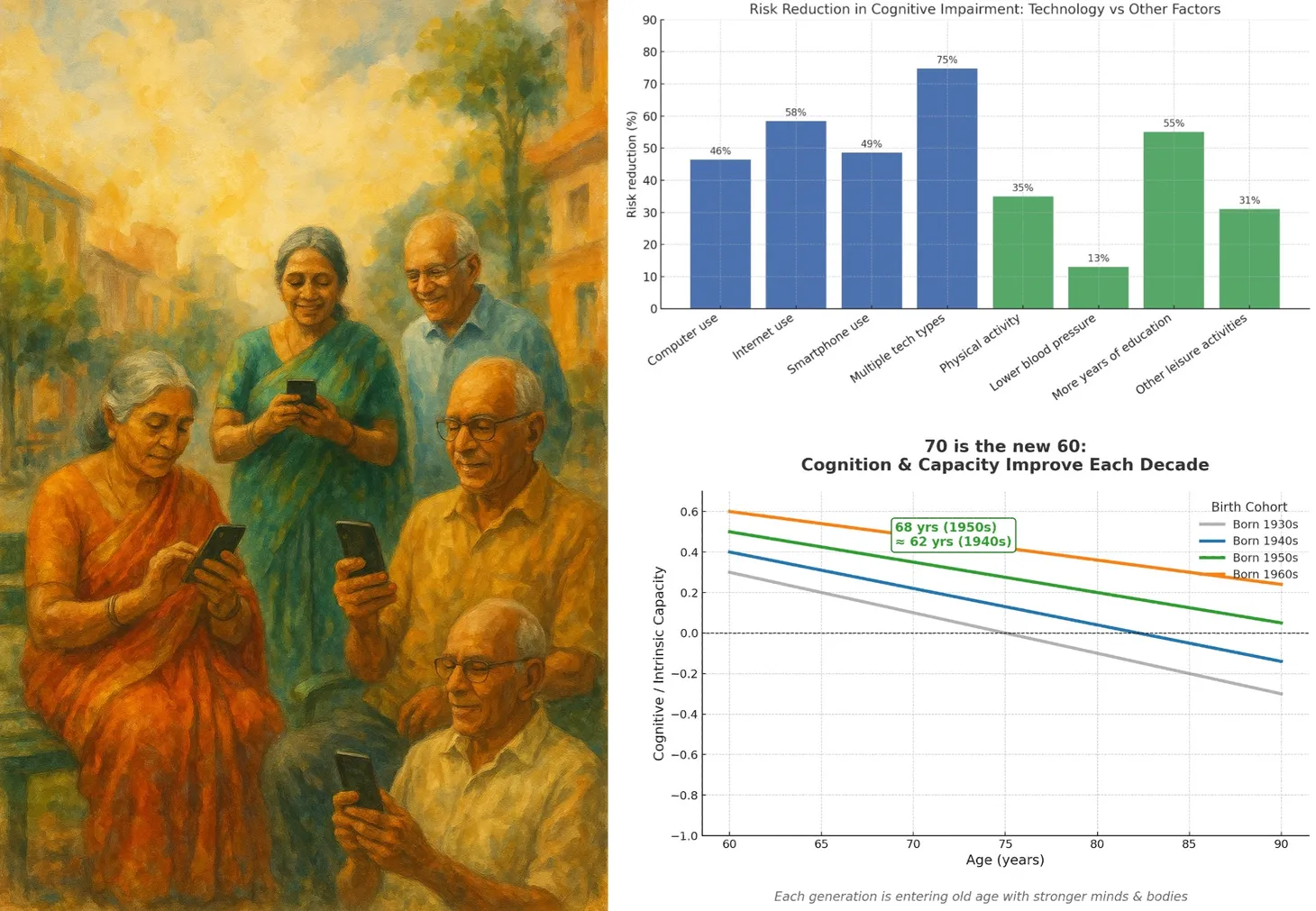

A new study that was published last year from Rush University [3] showed that those who started off with higher levels of cognitive activity and maintained them (average age at the start of the study was 79.7 years), developed dementia at least 5 years later than those who had lower levels of activity. These “cognitive” activities included reading, writing and playing games such as puzzles, cards, etc. Unlike the Nun study though, baseline education levels did not affect the rate of cognitive decline, though like in the Nun study, there was no correlation between cognitive levels and brain autopsy findings of dementia, reiterating that high cognitive levels may lead to the development of new neural pathways that help reduce the impact of pathologic deterioration (i.e. cognitive reserve).

So what about reading, specifically? And by that I mean reading seriously…novels, newspapers, magazines, etc…and not WhatsApp messages, Facebook posts and tweets?

A Taiwanese study in 2020 by Dr. Chang and colleagues [4] addressed only “reading” as an activity and found that it was protective of cognitive function. The accompanying editorial by Dr. Carol Chan [5] addressed the findings in more detail and touched upon the fact that a good body of literature now exists to support these conclusions. Since cognitive reserve can’t be measured directly, educational attainment and cognitive activities like reading serve as proxies to assess the extent of cognitive reserve and its protective ability.

A study from Allen Lee and colleagues out of Hong Kong [6] showed that active participation in intellectual activities including reading may help delay or prevent dementia. The accompanying editorial [7] however then touches upon the possibility of reverse causation.

Reverse causation means that if you are going to get dementia, because it occurs over a long, long time, the process itself may slow down your cognitive abilities and reduce your physical activity much before you actually manifest dementia, rather than the other way around.

A large recent study by Sarah Floud and colleagues [8] with an average of 16 years of follow-up and 789339 patients showed that it is likely that dementia causes reduced physical and intellectual activity much before the diagnosis of dementia and not the other way around. What they did not address though is whether these activities delay the onset of dementia. It is possible that we cannot prevent dementia, but if we can delay the onset as the Rush and Nun studies show, that should be good enough as well.

As Drs. Blacker and Wevue [7] then go to end in their commentary, while addressing reverse causation,

“In the meantime, is there any reason not to pursue cognitive (and physical and social) activities that can enrich our lives and those of people around us? Chosen well, such activities improve quality of life, and they might reduce our risk of dementia, too. On the other hand, do these data support the purchase of brain games software or toys? Only if the users find that such activities are engaging and worth pursuing—and purchasing—for their own sake. There is no evidence that such activities offer more benefit than a book from the public library, a game of chess in the local park, a penny-ante poker game, or a wide variety of other highly cognitive but close-to-free activities on offer.“

So what does that mean for you and I? Despite the spectre of reverse causation suggesting that if you are going to get dementia, you are going to get it and no amount of physical or intellectual activity will help, it is still very likely that reading and other similar cognitive activities and physical activity (given all the other benefits) make a big difference, if not in preventing dementia, then in delaying the age of onset and reducing the rate of cognitive decline.

Reading, in general, is on the decline. Perhaps it is worthwhile taking a little structured time out of our busy days to spend time with words, whether digitally (Kindle, etc) or preferably with paper-based books and magazines.

Footnotes

1. Medaglia JD et al. Brain and cognitive reserve: Translation via network control theory. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2017 Apr;75:53-64.

2. Iraniparast M et al. Cognitive Reserve and Mild Cognitive Impairment: Predictors and Rates of Reversion to Intact Cognition vs Progression to Dementia. Neurology. 2022 Mar 15;98(11):e1114-e1123.

3. Wilson RS et al.. Cognitive Activity and Onset Age of Incident Alzheimer Disease Dementia. Neurology. 2021 Aug 31;97(9):e922-e929.

4. Chang YH et al. Int Psychogeriatr. 2021 Jan;33(1):63-74.

5. Chan CK. Can reading increase cognitive reserve? Int Psychogeriatr. 2021 Jan;33(1):15-17.

6. Lee ATC et al.. Association of Daily Intellectual Activities With Lower Risk of Incident Dementia Among Older Chinese Adults. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018 Jul 1;75(7):697-703.

7. Blacker D, Weuve J. Brain Exercise and Brain Outcomes: Does Cognitive Activity Really Work to Maintain Your Brain? JAMA Psychiatry. 2018 Jul 1;75(7):703-704.

8. Floud S et al. Cognitive and social activities and long-term dementia risk: the prospective UK Million Women Study. Lancet Public Health. 2021 Feb;6(2):e116-e123.

Atmasvasth Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.