Our Health Matkas, Understanding Them and Then Taking Control

Understanding our health matkas and then taking control

You can listen to an audiorecording of this post by clicking on the Soundcloud track. You can listen to it in the browser itself.

My First Understanding of Health Matkas

It was 1984. I was a 2nd-year MBBS student, 18 months into my medical education, on my first “call” with Vidya, who was a few years senior and studying for her MD degree in internal medicine.

A patient, Kanti, who had developed acute paraplegia [1] the night before, began to gasp. A senior professor had made a diagnosis of Guillain Barre Syndrome (GBS)earlier in the day. GBS is a post-infectious immune disorder [2] that first affects the peripheral nervous system, and then the central nervous system. The paralysis had crept up his body during the day and had started to affect his respiratory muscles. Patients with GBS eventually recover partially or even completely. But sometimes they die. Often when they do, it is because of the paralysis of the respiratory muscles, which makes breathing difficult, as was happening with Kanti.

The treatment is quite simple. If we can manage the respiration by putting the patient on a ventilator, the patient can survive this acute episode and live.

There was no free ventilator in Sion Hospital [3] that day. Kanti died.

That night gave me my first understanding of the “matkas” of healthcare. If a functioning ventilator had been available that day, Kanti would have lived. But it was his unlucky draw of the lottery, a bad “matka” that led to his death.

Why was a ventilator not available? Because the functioning ones were already in use, and the two that were not functioning were waiting to be repaired. Sion Hospital is administered by the Mumbai Municipal Corporation, which had not paid the vendor. This situation was unlikely to change that year; the tender for buying new ventilators was stuck somewhere in the bureaucracy. Many more patients who needed ventilatory support had likely died as well because of their “matka” of being admitted to a hospital with an inadequate number of functioning ventilators.

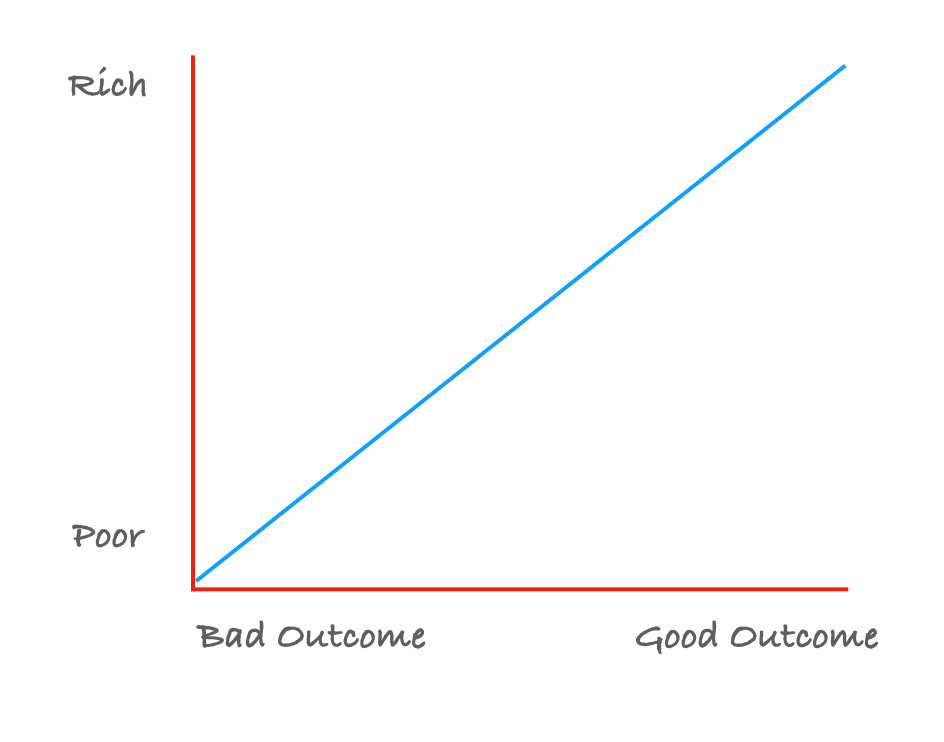

Kanti was poor, which is why he was in Sion Hospital. A similar patient with the means to go to a private hospital with enough ventilators, would have probably lived.

This is a simplistic representation. But basically, a rich person with resources would have access to a ventilator and a much better outcome as compared to a poor person without resources and access, like Kanti.

What is a Matka?

Matka is an earthen pot. In Mumbai, it is also slang for luck, based on a form of gambling, the “chit lottery” [4], where bets are place on chits, or notes of paper with numbers scribbled on them, pulled out from earthen pots. These “matkas” were much more popular in the latter half of the 20th century.

In Mumbai, when you win or experience a stroke of luck, we often say in colloquial Hindi, tera matka lag gaya; you have won the lottery.

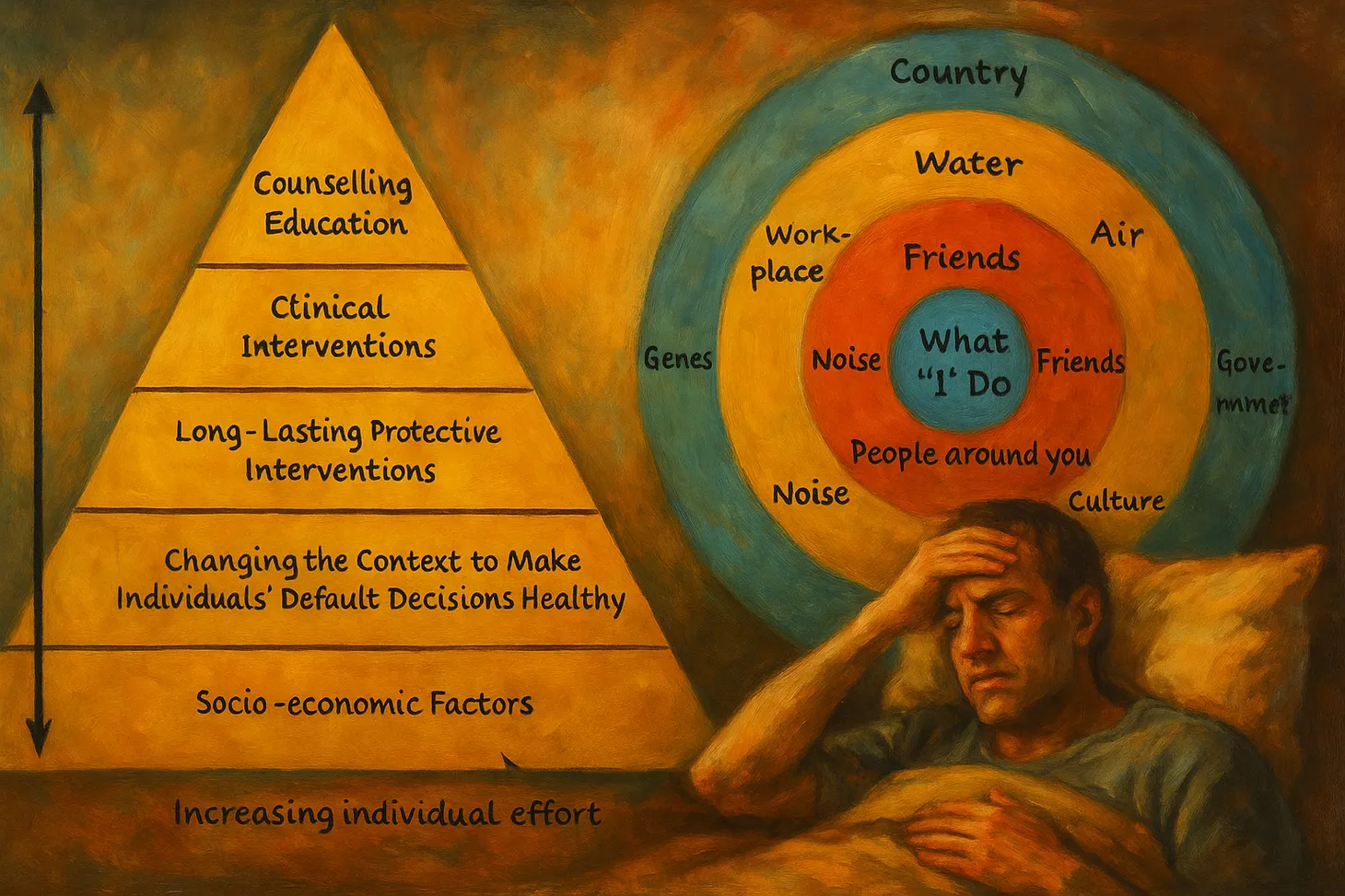

The Matkas that Affect our Health

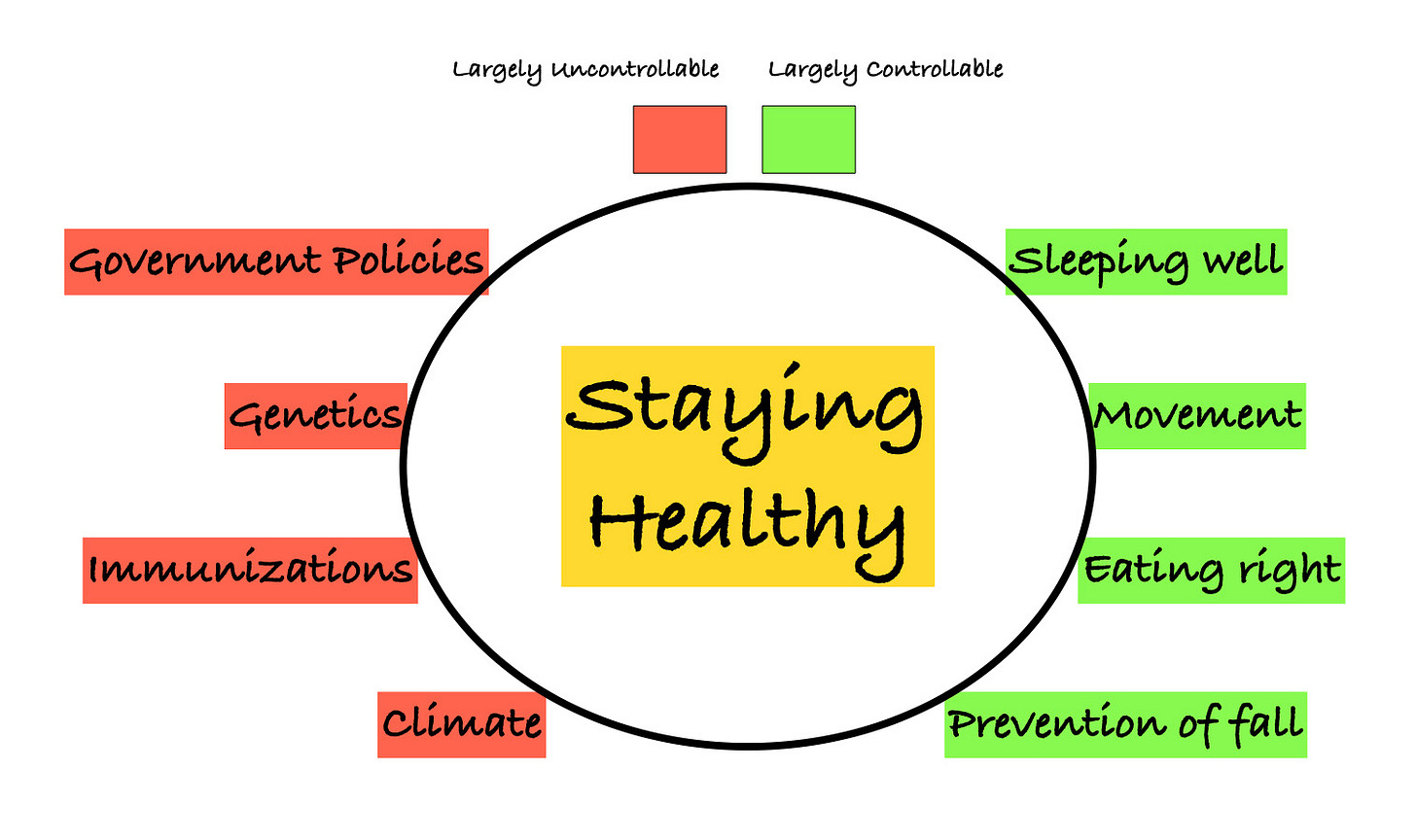

To some extent, our health is in our hands. There are many things we can control; eating right, exercising, meditating, not-smoking…all of these make a big difference to our longevity, our ability to be disease-free and our overall well-being, even if we are handed a poor set of genes and live in a bad environment. However, many other factors that determine our health, such as where we live, our socio-economic status, our gender, our genetic profile…are pretty much uncontrollable.

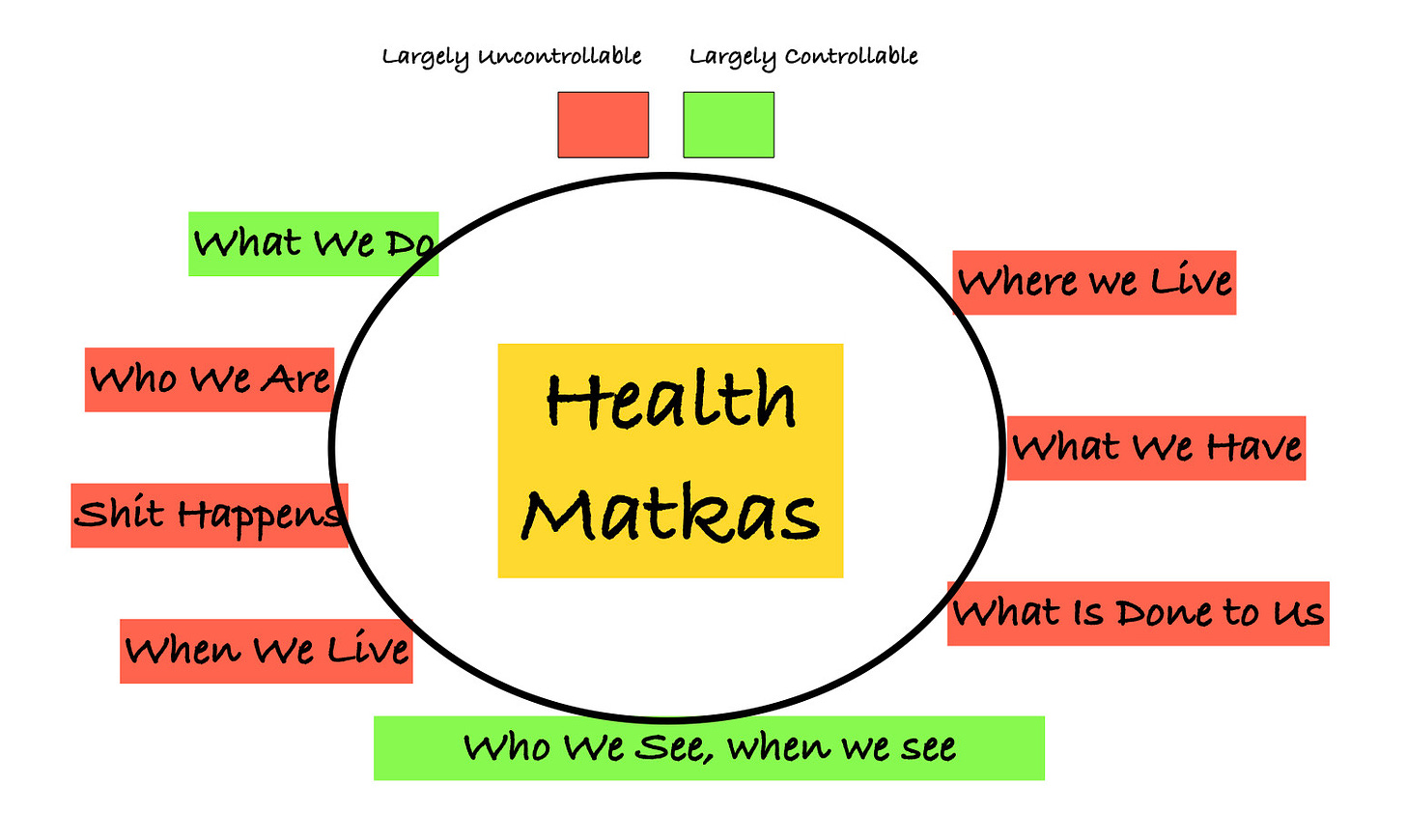

Matkas of Prevention, Matkas of Outcome, Controllable Matkas & Uncontrollable Matkas

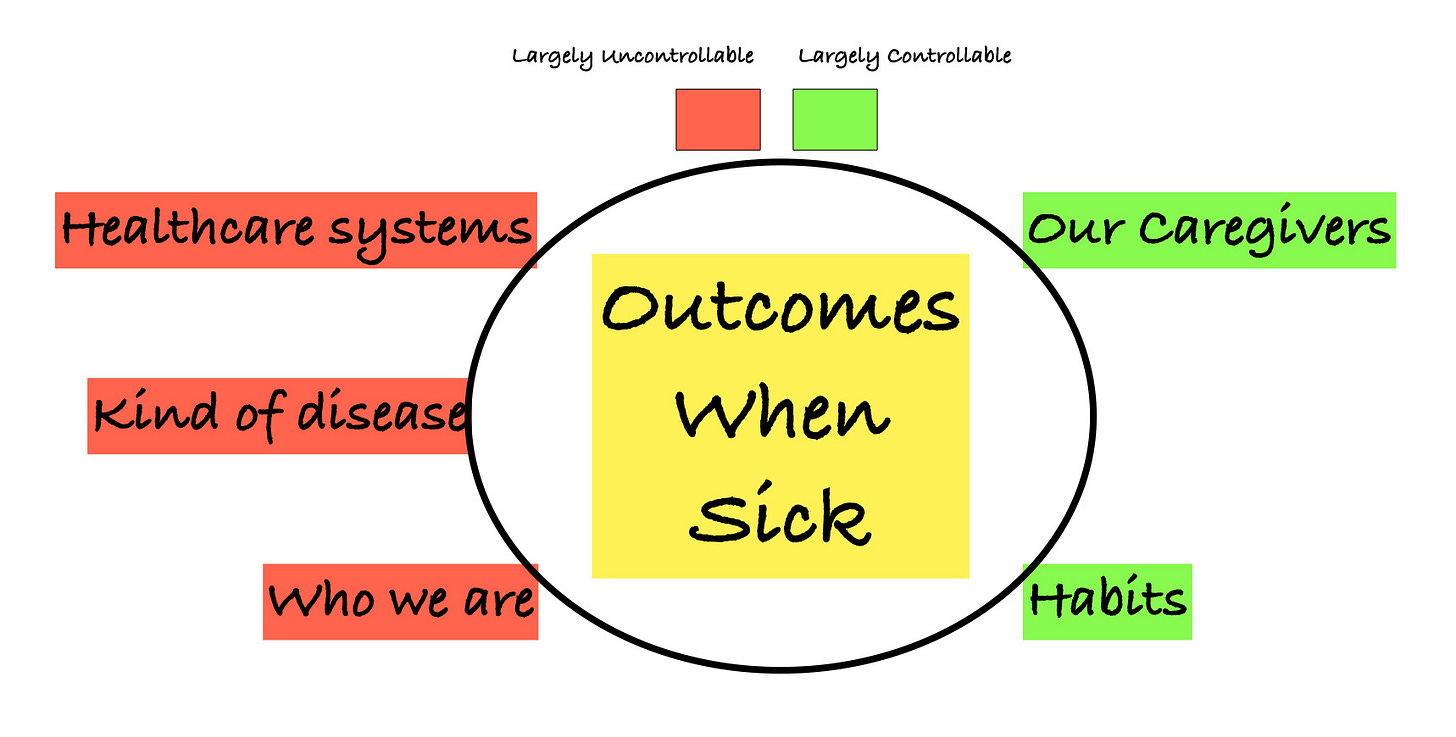

Broadly, our matkas can be divided into those that keep us healthy and prevent us from falling sick and those that affect how we do when we are felled with disease.

Within these, are then the ones we can control and the ones we can’t control.

For example, the country we live in (where we live), our healthcare systems (what is done to us), our genetic pool (who we are), are largely uncontrollable matkas. Knowing about them and their impact can help us understand how they can affect us. Similarly, our habits (what we do) or the doctors we see or the hospitals we go to (who we see, when we see) are largely controllable. The extent of control we have however varies depending on where we are and what we have; for e.g. insurance in the United States often dictates who we can see when we fall sick, which becomes an uncontrollable matka, whereas in India, who we go to is quite often a choice some of us are able to make on our own.

Many of the matkas that affect our health are uncontrollable and these decide when and if and how we will get sick or not.

For example, if the Govt is able to keep our environs clean and prevent mosquitoes from breeding, then the incidence of dengue and malaria would be drastically reduced, preventing us from falling sick and keeping us healthy. These issues are rarely in our hands unless we have the powers to change policies. However, if we eat right, exercise and sleep well, we can increase our chances of being disease free, especially when it comes to non-communicable conditions.

In the same vein, how we do when we fall sick is a combination of controllable and uncontrollable matkas.

Often, we have no say about where to go when we fall sick depending on the insurance or resources we have. Our outcome then depends entirely on whatever it is the system can offer. If, like Kanti, we or the healthcare systems don’t have adequate resources, we will have poorer outcomes than those with access to better healthcare delivery.

Using Covid-19 as an Example

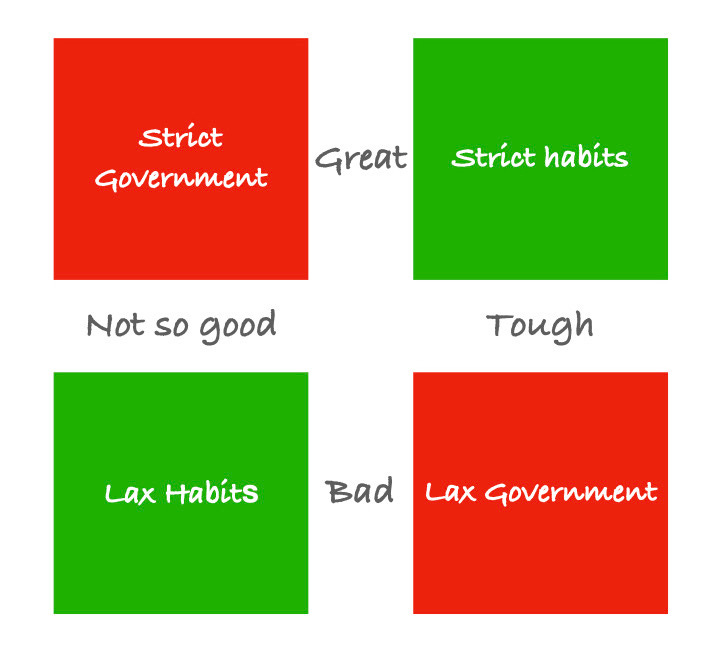

Whether we get infected or not is often uncontrollable and depends on the policies of the Government and authorities; the intensity of the lockdown, the laws governing large gatherings, the ability to enforce mask-wearing, etc. What we can control however, is who we meet or see, and how we behave; whether we wear masks or frequent indoor bars or stay at home, etc.

When it comes to getting infected with Covid-19, Government policies and societal behavior trump individual actions…this means that uncontrollable matkas are more important than controllable matkas. For e.g. a New Zealander who disobeys the law is likely to have a smaller chance of getting infected than a person in Brazil who decides to follow all the right procedures for personal protection but is in an environment where everyone does what they want.

How we do if we get infected also depends on controllable and uncontrollable matkas. If we are young (uncontrollable), have no co-morbidities (party controllable), we do well. If we don’t have enough doctors or nurses (uncontrollable), or if drugs are in short supply (uncontrollable), we don’t do well.

Taking Control

We have been primed from childhood to believe that our health has to be managed by “doctors” and/or the “healthcare system”. Hence, the vast majority of us forget the physiology and anatomy of our bodies, the moment we finish school and most of us have no clue where the pancreas is or what the pituitary does.

This is ridiculous.

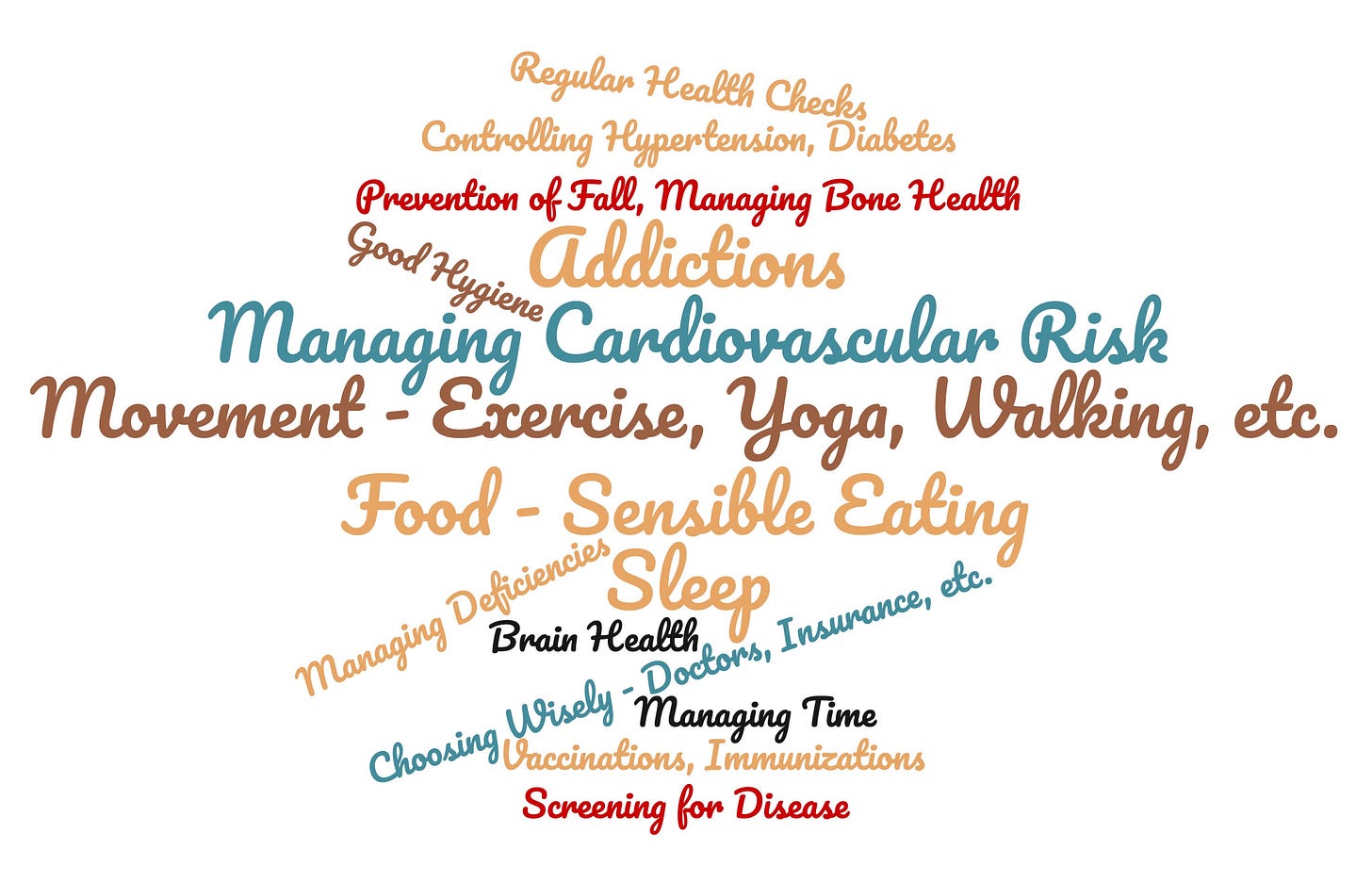

Every individual must be able to take care of their health, especially when it comes to prevention and the control of common conditions like hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, etc.

While there are uncontrollable matkas that we can’t do anything about, there are many factors that we can control and should take control of.

The main aim of this newsletter is to empower all of us with the information needed to be able to take control of our own health and lives within the context of an understanding of the various controllable and uncontrollable matkas that affect us.

One post at a time, in no particular order, we will discuss the various “hacks” that can help us lead a healthy life.

Why This Newsletter

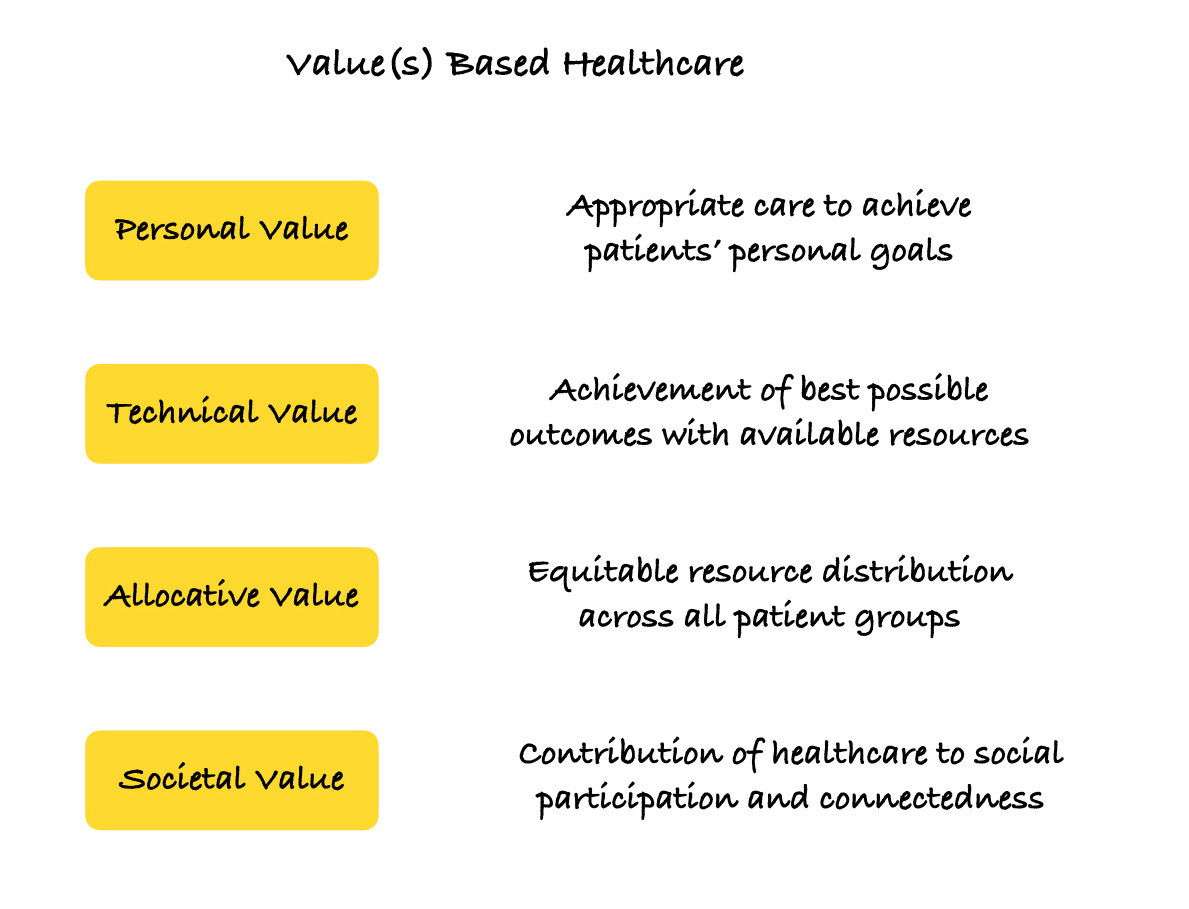

Value(s) based healthcare [5] in a recent European Commission article [6] redefines the way healthcare is delivered so that appropriate care is delivered to achieve our individual or group goals, using available resources in the best possible way, equally allocated across all groups, within the society in which that healthcare service is based, be it a specific region or a country or even a continent.

This is similar to a definition of “Ideal Health” that I subscribe to.

The ideal healthcare state

- ensures that disease prevention and health preservation services and advice are available to all people at all levels of income, after taking into account genetic, racial and ethnic differences,

- ensures that when sick, the same level of treatment is available to everyone, at all times of the day, week and year,

- ensures that healthcare workers have a thorough, in-depth understanding of disease processes and that they follow current guidelines and standard operating procedures (SOPs) for diagnosis and treatment that are tailored to the individual’s genetic, socio-economic and environmental situation, and

- ensures that there is shared decision making with the patient and their guardians and family or friends as the case may be.

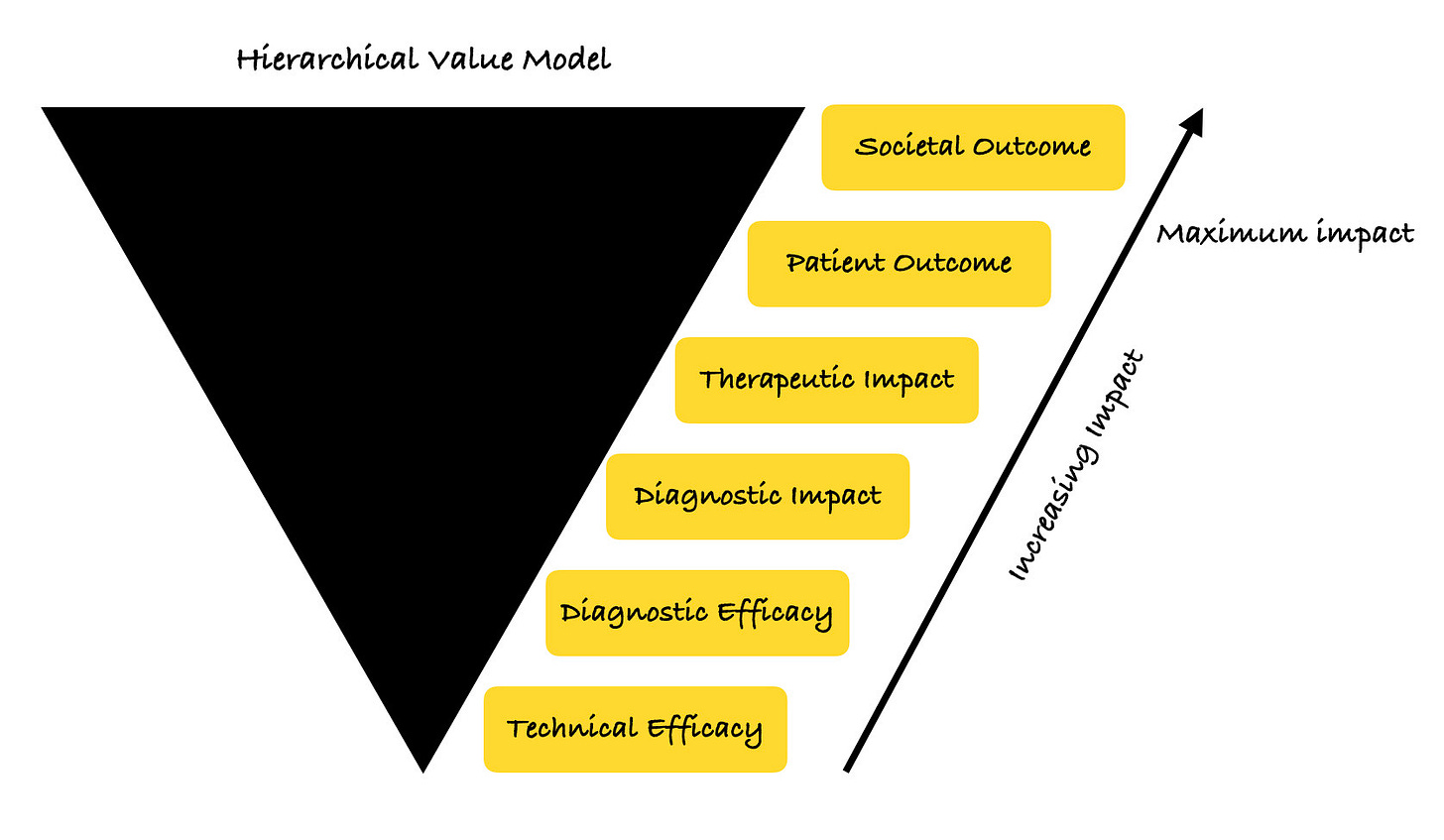

Almost 30 years ago, in 1991, Fryback and Thornbury [7] described a hierarchy to assess the usefulness of a diagnostic test, a concept that can be widened to include any aspect of healthcare.

The problem with all these models, despite all the talk of patient centricity, is that they are all top-down; created by bodies and institutions that believe they know better. Ideally, all such models must also include empowered patients and people who can also make decisions to improve or worsen their own health.

My submission is that knowledge and healthy habits can go a long way in helping us take control of our various matkas, and by talking about these issues in this newsletter, I believe we can make a difference to our individual health outcomes. This is the value proposition that this newsletter will offer week after week, month after month, talking about the good and bad matkas, and the steps needed to control them, in an attempt to be and stay healthy.

Footnotes

1. Acute paraplegia means sudden paralysis of both lower limbs. Quadriplegia is when all 4 limbs are paralyzed. Hemiplegia is when one half of the body is paralyzed.

2. Immune disorders are diseases of the immune system that can affect different organs of the body. These may occur due to reduced immunity or due to the immune system reacting against perceived foreign agents or antigens by producing antibodies that while attacking the antigen, also attach tissues of the body and lead to diseases.

3. Sion Hospital - popular name for Lokmanya Tilak Municipal General Hospital (LTMGH)

4. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Matka_gambling

5. Brady AP, Bello JA, Derchi LE, Fuchsjäger M, Goergen S, Krestin GP, et al. Radiology in the Era of Value-Based Healthcare: A Multi Society Expert Statement From the ACR, CAR, ESR, IS3R, RANZCR, and RSNA. Journal of the American College of Radiology. 2020 Dec;S1546144020313491.

6. European Commission Expert Panel on Effective Ways of Investing in Health (2019). Draft opinion paper on “Defining Value in ‘value- based healthcare’”. https://ec.europa.eu/health/expert_panel/sites/

expertpanel/files/024_valuebasedhealthcare_en.pdf.

7. Fryback DG, Thornbury JR. The Efficacy of Diagnostic Imaging. Med Decis Making. 1991 Jun;11(2):88–94.

Atmasvasth Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.