Why We Live Longer and Better

Why we live longer and better

In the last piece, I explained why we all are living longer and doing better than people born just a 100 years ago. I ended with this question.

How did this happen? What dramatic changes in the last 200 years compared to the prior 30,000 years led to an improvement in the health and longevity of every human being on this Earth along with increasing prosperity and growth so that we managed to reach a total of 7.5 billion people on this planet?

This post is free to read, but you will need to subscribe with your email ID to read the rest of the post.

The Healthcare Pyramid

Some years ago, I was sitting with some school-friends of mine and as often happens in such situations, we started discussing the state of the world. The conversation drifted to healthcare in India and Mumbai, each friend coming out with some horror story or the other of their unhappy interaction with doctors and hospitals. At some point I mentioned how much better off we now are than the people of the last century. Everyone immediately agreed, harping on the improvements in technology and modern medicine that according to them, have revolutionized healthcare delivery and improved longevity and individual health. They meant advances like robotic surgery, PET scans and the like.

This misunderstanding that modern healthcare delivery and doctors and hospitals are the ones responsible for these gains is widespread and likely occurs because we view health and healthcare through the prism of our own experiences, which invariably revolve around nurses, doctors and hospitals. A survey by Gordon Lindsay and his colleagues in the US [1]showed that almost 80% of the people they polled ascribed the improvement in overall health to the wizardry of modern medical care alone.

Unless we work in healthcare and allied fields, we rarely have a concept of public policy and epidemiology, though we are now better informed, thanks to the Covid-19 pandemic. Many more people, all of a sudden have become aware of the importance of social, economic and political factors that drive overall public health, than ever before…and epidemiologists are suddenly hot property [2].

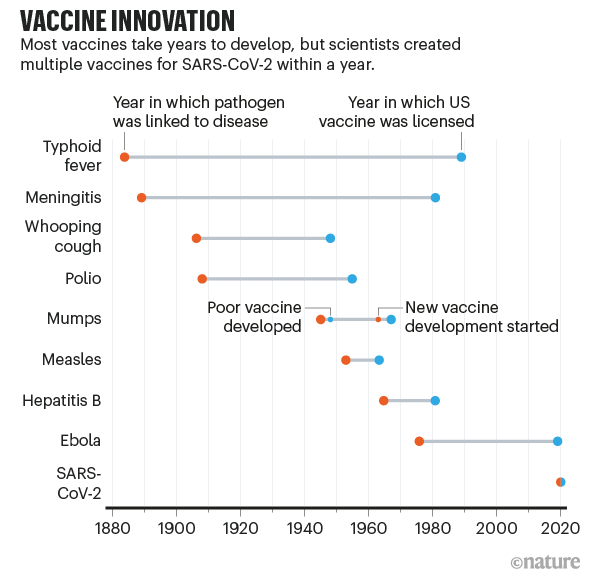

Where advances and wizardry have made a difference in Covid-19 times, is the dramatically reduced time it has taken to prepare the vaccine [3]. While this has involved clinical doctors for running phase III trials, the main work has been done by researchers and PhDs. And while frontline doctors have saved individual lives, the large “saves” at a population level have come from wearing masks, distancing and hygiene, to which vaccination is adding another layer by protecting people from getting infected and if infected, preventing spread.

The predominant determinants of improved health, life expectancy and reduced mortality rates over the last 200 years have primarily been socio-economic and political; reduction in poverty, better education, clean water, better sanitation, adequate nutrition, immunization and the use of antibiotics.

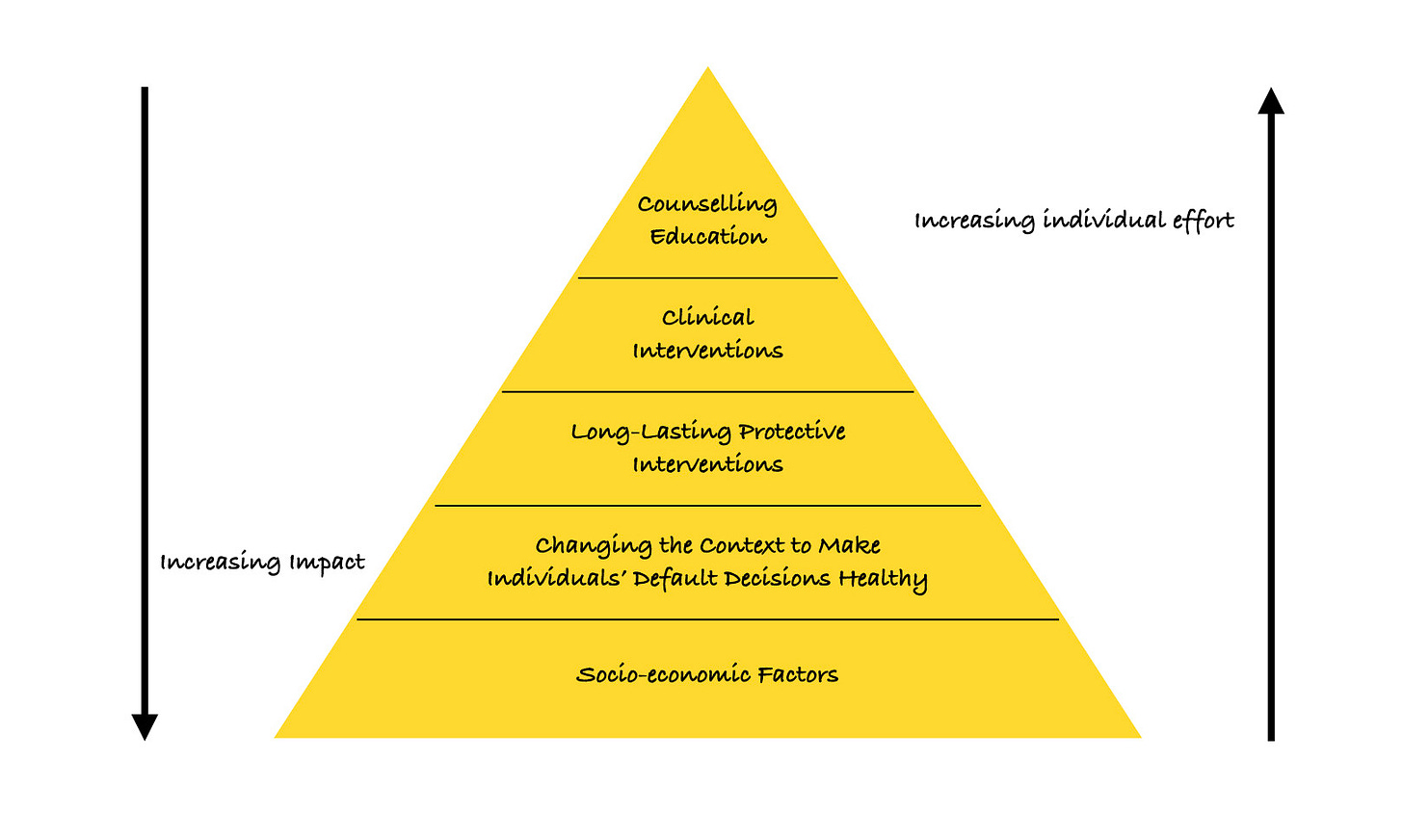

Thomas Frieden, chief of the Centre for Disease Control (CDC), from 2009 to 2017, in an article in 2010 summed this up well with a 5-tier pyramid showing that as solutions and interventions shift from populations to individuals, lesser is their impact [4].

At the bottom are socio-economic factors, changing which have a wide impact on a large number of people, with minimal personal / individual effort needed. These essentially include clean water, better sanitation, improved incomes, increased literacy and better nutrition, all of which are a result of political intervention and directed growth. In recent times, the Swachh Bharat Mission [5] is an example. While it will take time to assess its impact on longevity and reduction of diseases, one recent study from Jodhpur has shown a reduction in acute diarrheal disease in 2017 and 2018 because of the increasing use of the new toilets built as part of this Mission [6].

The next tier is the one where decisions are taken in the interest of individuals by the Government or similar bodies to create a “default” healthy situation, e.g. banning artificial trans-fat in food by legislation to improve cardiovascular health or banning cigarette smoking in all confined places to reduce smoking related illnesses or making helmets for two-wheeler riders and seat-belts for four-wheeler drivers and passengers mandatory to reduce accident related deaths. The effort needed by people to circumvent these default healthy decisions is much more than complying, so the vast majority will comply with the law and benefit from the resultant improved health conditions. A recent example would be the measures initiated by Governments to reduce the spread of Covid-19 with masks, distancing and in some instances, “lockdowns”, which have potentially saved more lives by preventing the disease as compared to those saved by doctors after people have been infected and admitted in Hospitals [7,8].

The third tier is that of long lasting protective interventions such as vaccinations or screening programs such as mammography, where the impact is significant, but involves reaching out to people as individuals, who often have the choice to forego the procedure, for a variety of reasons, even if known to be useful. At the time of writing this, we can see that at least in Mumbai, 40-50% of the target population is hesitating [9] to take the vaccine and a roll-out that was intended to vaccinate a large number of frontline workers and healthcare professionals has faltered - simply because when people have the ability to choose and decide not to get vaccinated, the impact is lower than if there was a “default” situation as in the second tier, with no choice.

Then come clinical interventions where doctors and hospitals and the healthcare system interact directly with patients and people to diagnose and treat, followed by the last tier of education and counseling. While doctors and hospitals do make an impact, they do so at an individual level, where the impact is obviously great for that particular individual and their family, but minor at a population level, as we have also seen with the Covid-19 pandemic. It is better to prevent the disease in the first place than treating patients when they become sick.

We are healthier than ever before in the history of humankind. But this is poor solace to those who land up with pain and suffering or contract diseases that lead to premature death. Despite our overall health gains worldwide, our individual health still gets determined by our genes, the environment around us, the choices we make in life, our access to healthcare systems and then the diagnosis and treatment we receive when we fall sick. All of these are our matkas - situations that affect our individual health and our longevity; some of which we have no control over, while some we have the power to change, as we will see in the next few articles.

Footnotes:

1. 1. Ray M Merrill GBL. The Contribution of Public Health and Improved Social Conditions to Increased Life Expectancy: An Analysis of Public Awareness. J Community Med Health Educ [Internet]. 2014 [cited 2020 Feb 5];04(05). Available from: https://www.omicsonline.org/open-access/the-contribution-of-public-health-and-improved-social-conditions-to-increased-life-expectancy-an-analysis-of-public-awareness-2161-0711-4-311.php?aid=35861

2. https://www.chronicle.com/article/Exhausting-Very/248309

3. https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-020-03626-1

4. Frieden TR. A Framework for Public Health Action: The Health Impact Pyramid. Am J Public Health. 2010 Apr;100(4):590–5.

5. https://swachhbharatmission.gov.in/sbmcms/index.htm

7. https://gh.bmj.com/content/5/5/e002794

8. https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-020-02801-8

9. https://www.thehindubusinessline.com/news/covid-19-vaccine-hesitancy-responsible-for-low-turnout-in-india/article33615039.ece

Atmasvasth Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.