When We Live - The Matka of Better Life Expectancy

There has been no better time to be alive from a health perspective than now with ever-increasing lifespans and healthspans

This decade is the healthiest we have ever been. This may seen an anachronism in this era of Covid-19, but read on.

Lifespans

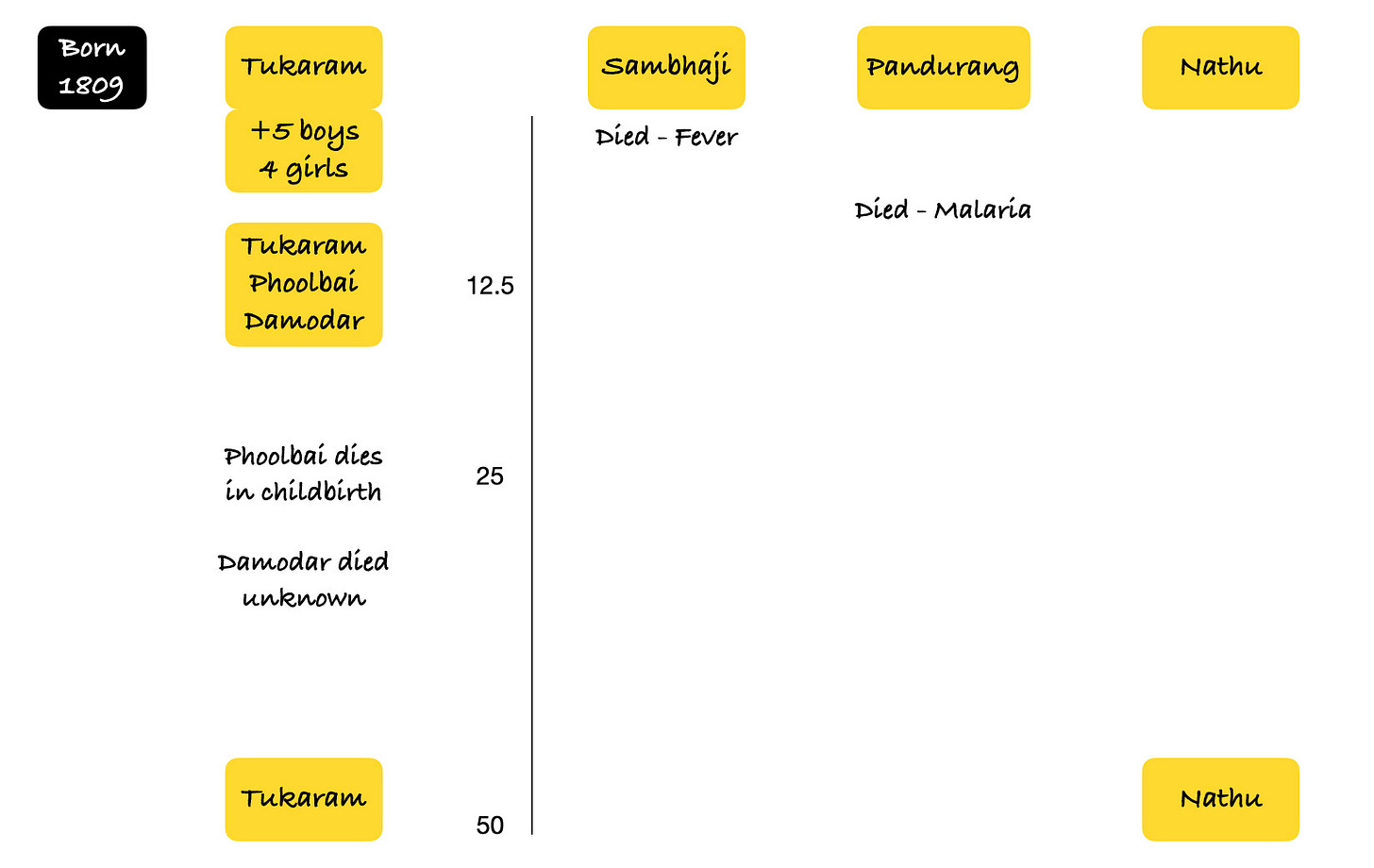

Tukaram was born in 1809, on the same day as Sambhaji, Pandurang and Nathu, in a small village in Maharashtra. Within a year, Sambhaji was dead of a mysterious fever, and Pandurang died of malaria at age 8, leaving just Tukaram and Nathu [1]. Tukaram was one of ten children, four of them girls, born within a span of 12 years. Five of his siblings did not make it past their second year of life and when he hit his teens, only Damodar and Phoolbai were still alive with him.

Tukaram’s peers in almost all the other countries of the world at that time shared the same fate, with survival a shade better in Belgium, Germany and the United States.

This post is free to read, but you will need to subscribe with your email ID to read the rest of the post.

My grandfather, Ranmal, who was born in the late 1890s was one of 7 children. My father tells me that Ranmalbapa had many other siblings…no one remembers the number. My father is one of 8 siblings as well, with 5 brothers and 3 sisters and at least 2 or 3 others (they also lost count) who did not make it beyond the first 2-3 years.

In 1809, the population of the world was around 1 billion, with a fertility rate of between 4.5 and 6.2 [2], and a child mortality rate of around 50%, which ensured that the population remained static/stable at that number with births and deaths pretty much canceling each other out. Since there was so much uncertainty about which and how many of their children would reach adulthood and because many hands were needed to help in the farms in these primarily agrarian communities, it was not uncommon for women to bear 10-15 children over their reproductive period with the hope that at least 3-4 would survive into adulthood.

By the time my grandfather was born in the late 1890s, despite the poverty they lived in, the child and infant mortality rates had already started dropping and the world population had risen to 1.6 billion.

Today, in 2020, we are 7.7 billion people, with a global infant mortality rate down to 2.9 % with just 4.6 % of these children dying before the age of 15 [3]. Despite our perceptions, and notwithstanding the Covid-19 pandemic, life expectancy and virtually all other health parameters have markedly improved globally as compared to just up to 200 years ago.

This is amazing progress. For over 30,000 years, human health pretty much mirrored the situation in 1809 with high fertility, high child mortality and an average life span between 20 to 40 years. And then within a short span of just 200 years, everything changed. Despite the significant global discrepancies and inequalities due to geographical, environmental and income-related differences, even the poorest of poor countries are better off than just 100 years ago.

So how does this “matka” apply to us? Just being born in these times is a positive, a big positive matka when it comes to longevity and life expectancy.

Tukaram and Nathu made it to age 50, but did not make it past age 55. Damodar died at the age of 30 and Phoolbai died in childbirth at age 25.

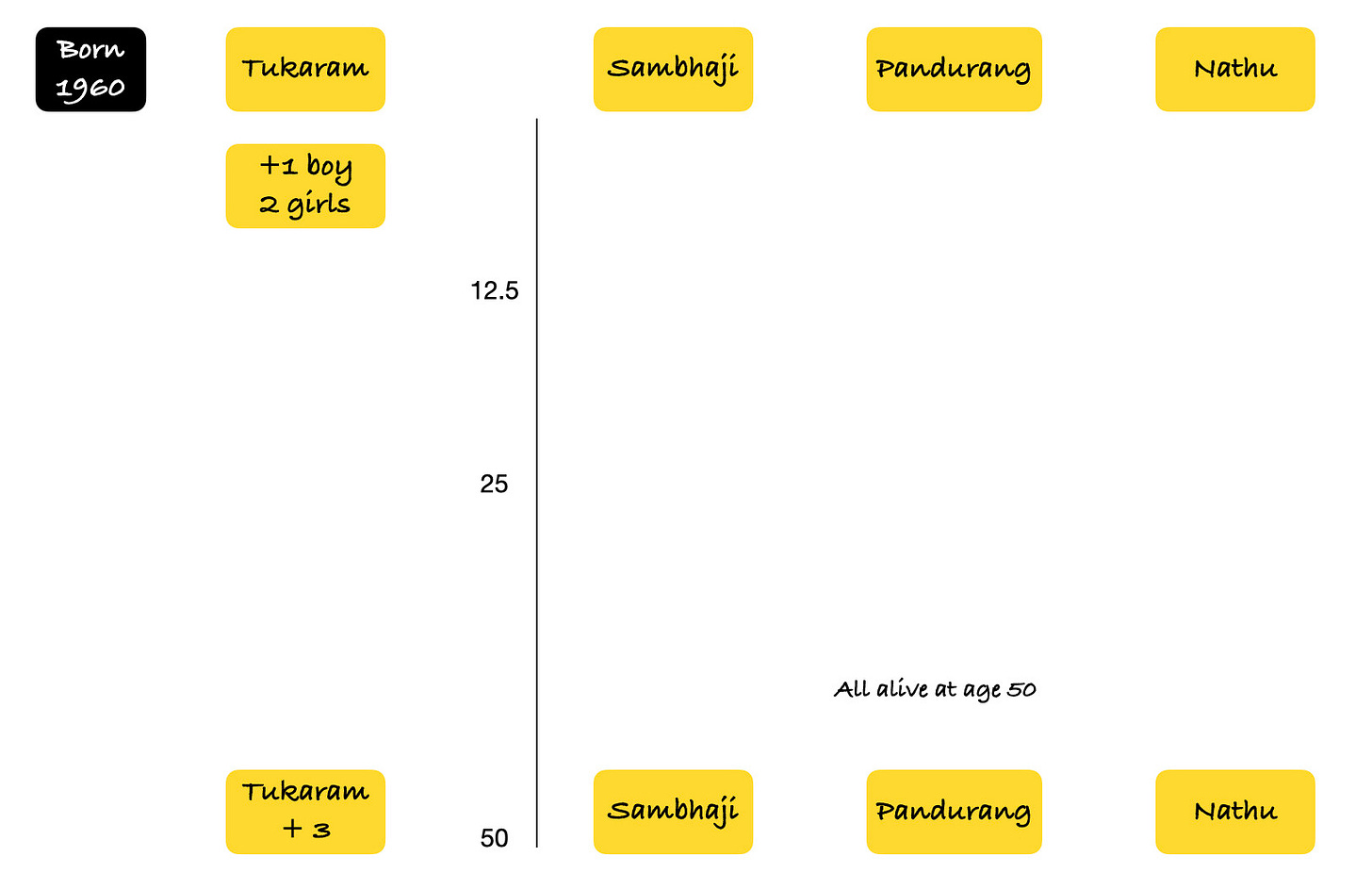

However, if Tukaram and his friends and siblings had been born in the 1960s instead of 1809, all of them would likely be alive today. The average life expectancy globally in 1809 did not exceed 40 years and that too is likely an overestimation [4]. Currently, in 2020, people across the world live an average of 72.6 years. It is a little lower in India at 69.7 years, but get this…every country in the world today, even the one with the lowest life expectancy (Central African Republic at 53 years) is better off than the country with the best life expectancy rate in 1809 (Belgium - 40 years).

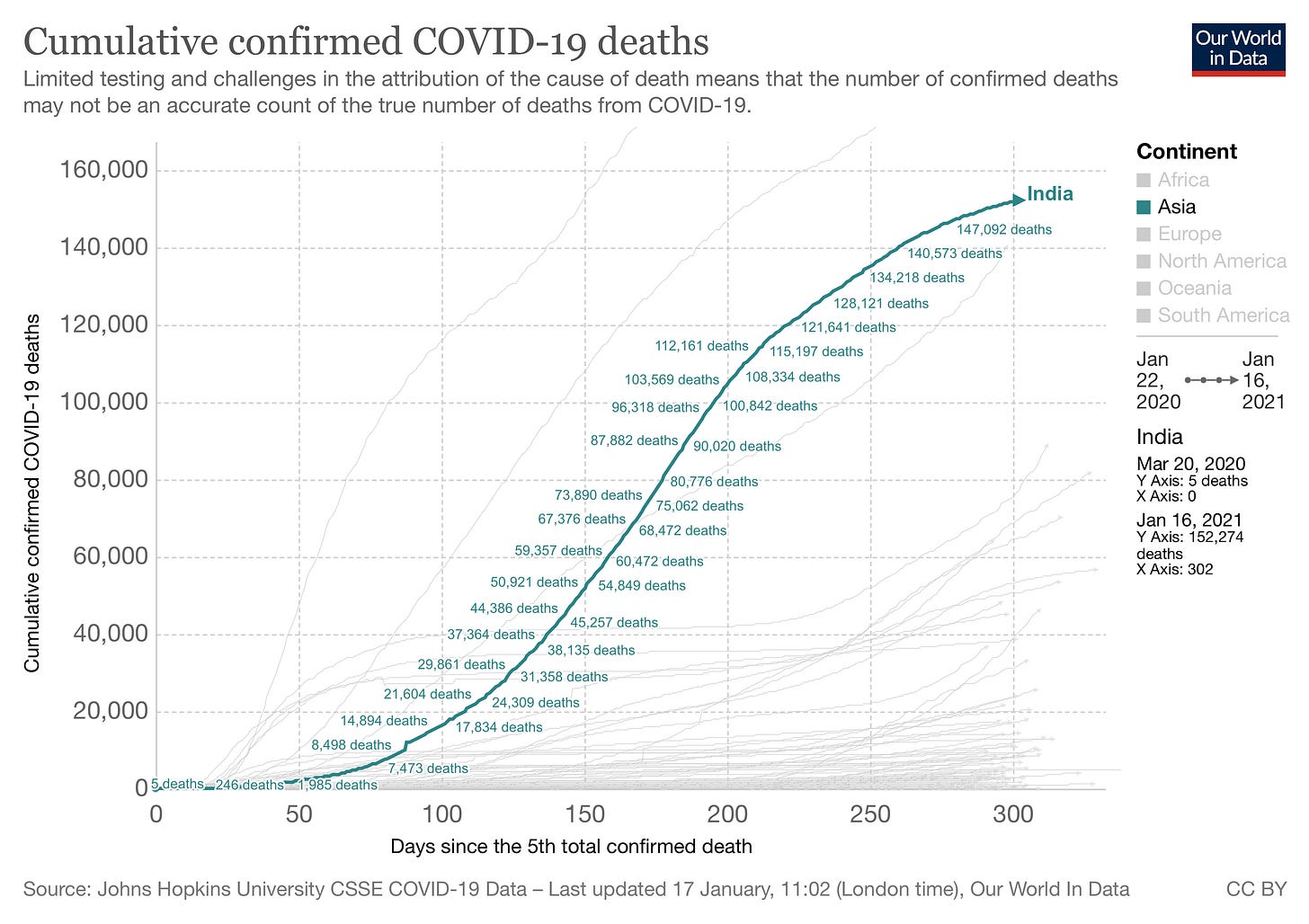

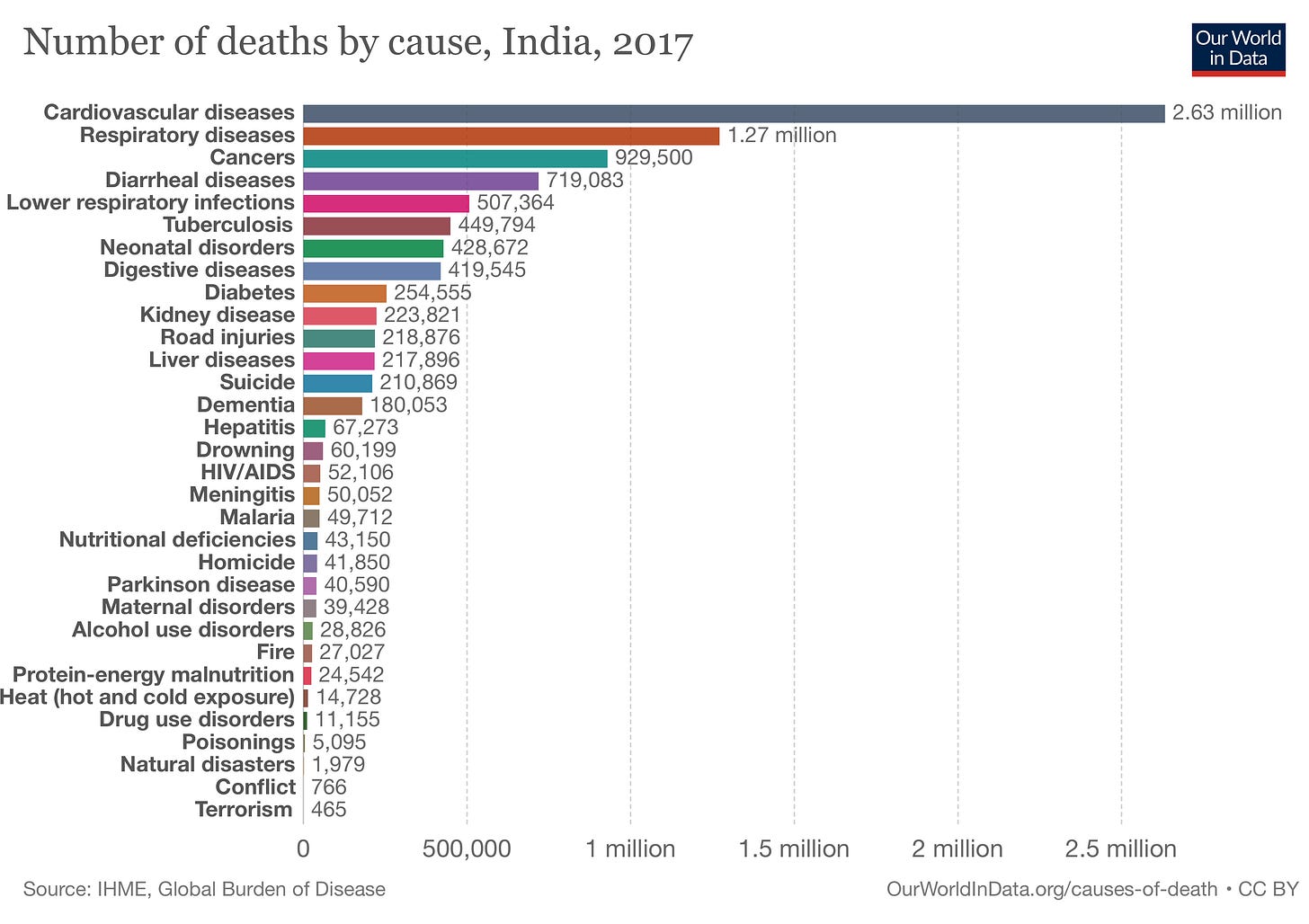

COVID-19 is likely to reduce life expectancies worldwide, though the exact impact will be known only when thing settle down. However, in countries like India [5], where the current number of deaths is 152,311 (as of Jan 17th, 2020) [6] , it will still be the 15th most common cause of death [7], between hepatitis (67,000) and dementia (180,000), (2017 data), which will likely not affect the life expectancy in India to any great extent.

How did this happen? What dramatic changes in the last 200 years compared to the prior 30,000 years led to an improvement in the health and longevity of every human being on this Earth along with increasing prosperity and growth, that we managed to reach a total of 7.5 billion people on this planet?

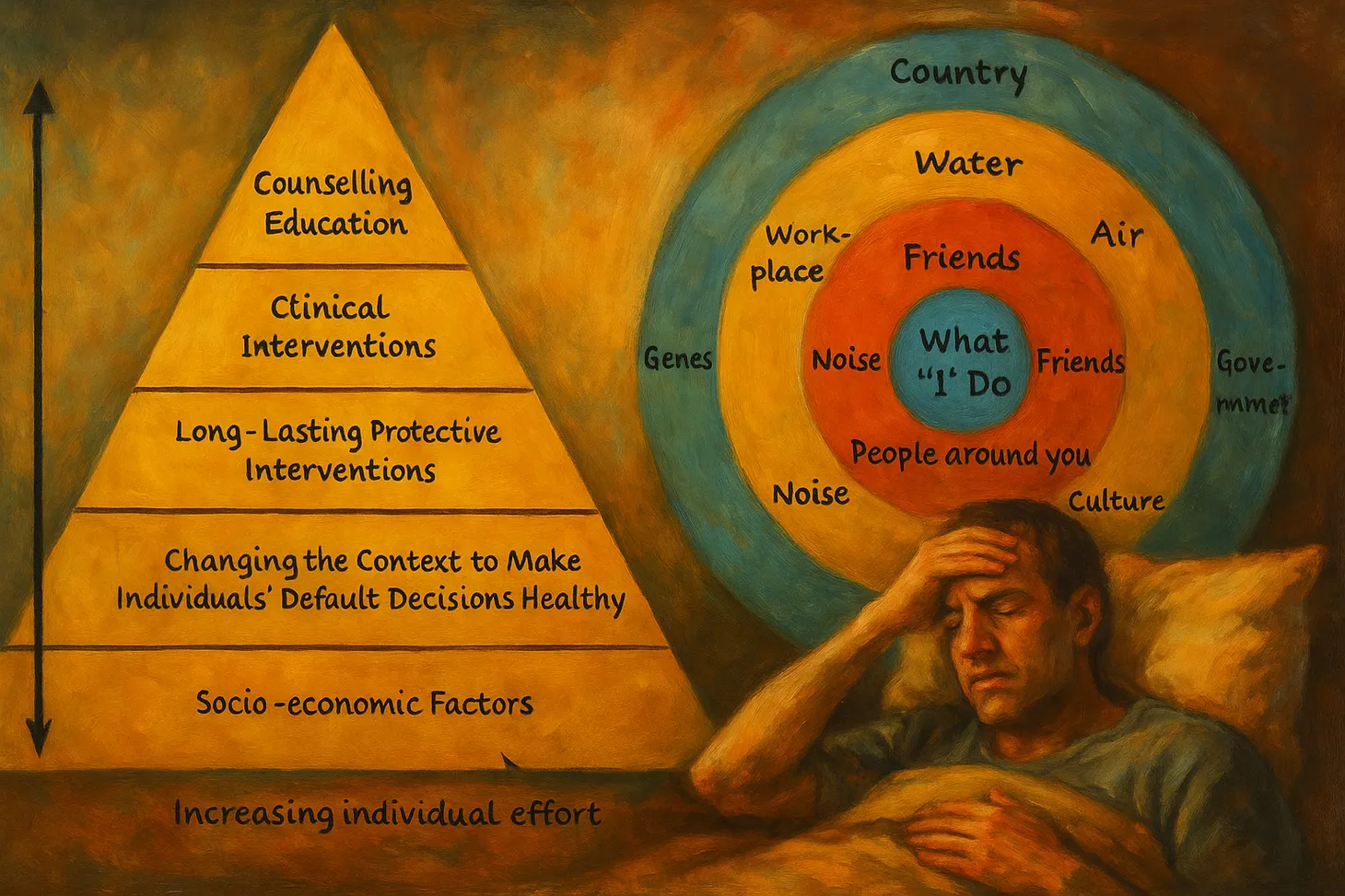

This needs an understanding of the healthcare pyramid and the various factors that affect our health as a group of people. I will discuss this next.

Footnotes:

1. https://ourworldindata.org/child-mortality

2. https://ourworldindata.org/fertility-rate

3. https://ourworldindata.org/world-population-growth

4. https://ourworldindata.org/life-expectancy

5. https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus

6. https://www.covid19india.org

7. https://ourworldindata.org/causes-of-death

Atmasvasth Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.