Where are Our Doctors?

We don't have enough doctors in India adding to the quadruple whammy of living in India

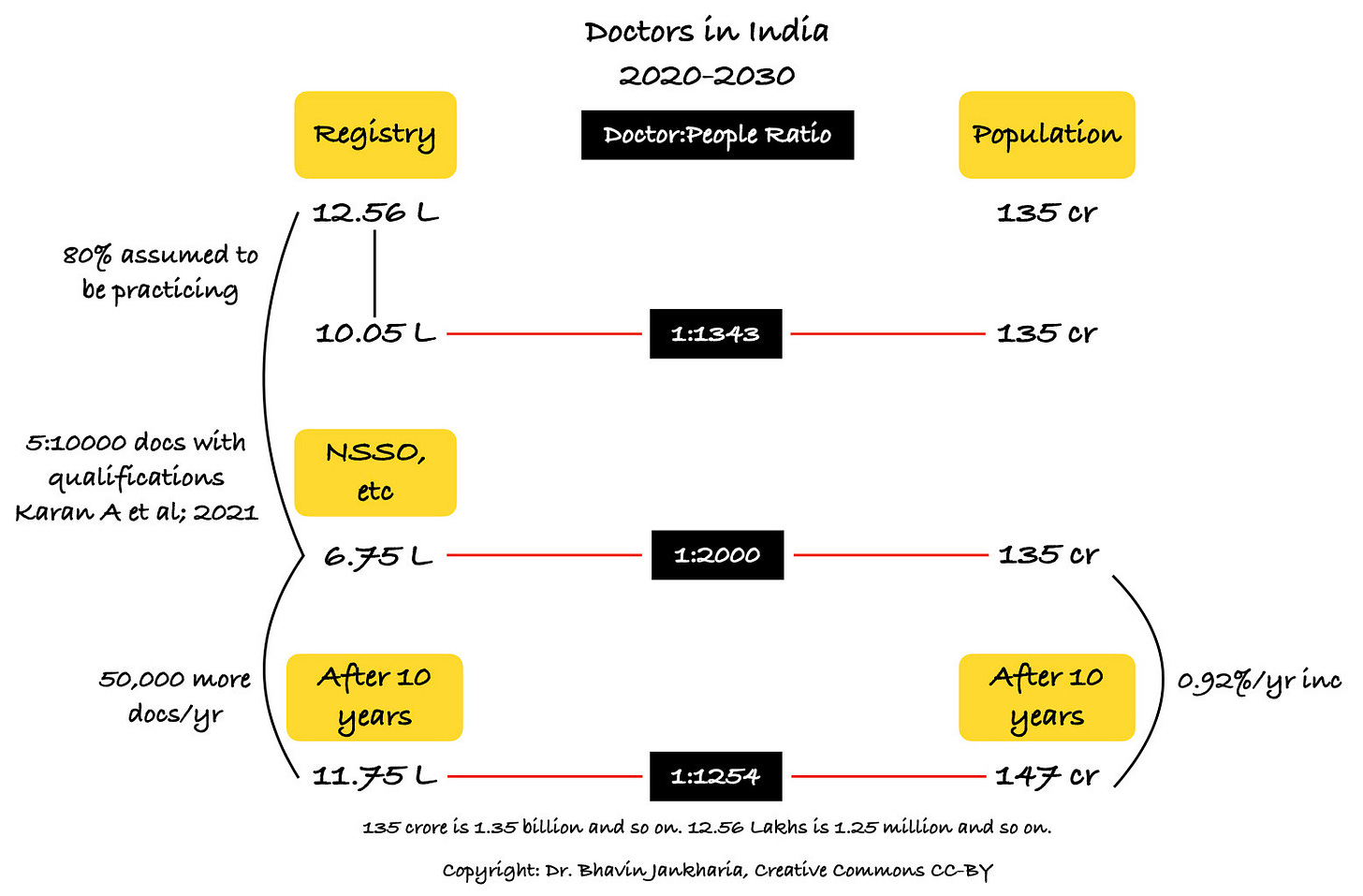

Dr. Robert Baid McClure has the distinction of holding the Maharashtra Medical Council (MMC) registration number of 1. He died aged 90 in 1991 in Canada. He is part of the “stock” of 1.255 million (12.56 lakh) doctors listed in the Indian Medical Registry as of September 2020 [1], of which an arbitrary 80% is supposed to be currently practicing (1.05 million or 10.05 lakhs), giving us a doctor:patient ratio of 1:1343, for a population of 1.35 billion (135 crores). Dr. Ramchandra Shivaji Poredi is the first entry (No 100) in the Bombay Medical Council (now defunct). He was registered in 1913. He too is not alive. He is also part of the same stock of 1.255 million doctors.

Both doctors are part of the arbitrary 20% of doctors who are considered to have died or retired or stopped practice or have never practiced or have migrated. In reality though, we have no clue. No one really knows how many doctors are actually practicing in India, i.e. are part of the “living/practicing” list of doctors. No one!! We have no tracking mechanism once a doctor has been registered in their respective state medical council.

Multiple papers over the last two decades have shown that the situation is actually quite dire. The most recent is from Anup Karan and his colleagues from the Indian Institute of Public Health [2] that compares the National Health Workforce Account (NHWA) numbers (taken from the Indian Medical Registry) with the numbers from the census and the National Sample Survey Office (NSSO) of 2018. The articles suggests that the number of living and practicing “qualified” doctors is likely 675000 (5:10,000), which is an availability of just 53% of those registered (another 148000 odd are “doctors” but unqualified and likely quacks). So our doctor:patient ratio drops to 0.5:1000 or 1:2000.

We might turn around and say that the situation is likely to improve significantly. After all, we have the largest number of medical colleges in the world (554) and an intake of 83075 students per year as of March 2021 [3]. Assuming that 80% of these students complete their MBBS, we would have 66460 doctors added to the workforce and even if just 25% of them migrate or don’t practice, we would add at least 50000 doctors per year.

But the population is also growing at 0.92% (13 million or 1.3 crores more people) every year. In 10 years, we would at best get to 1.175 million (11.75 L) doctors, which would bring us to a ratio of 0.69:1000 or 1:1294, which is still just not good enough, given the fact that the population is also aging considerably and would have aged even more in the next 10 years.

And we are not even considering the new WHO norms of 44 healthcare workers (doctors, nurses, technologists) per 10,000 population [4]. We are barely halfway there and will not get there even after 10 years. And it is the same story with nurses (just double the doctor numbers) and technologists. In comparison, Qatar has the highest D:P ratio in the world of 7.7:1000, with Cuba at 6.7:1000, Spain at 4.9:1000, Switzerland at 4.0:1000, Australia at 3.2:1000, China at 1.5:1000 and Bangladesh at 0.3:1000.

The chart below summarizes these doctor numbers.

This post is free to read, but you will need to subscribe with your email ID to read the rest of the post and to listen to the accompanying audio/podcast.

You can listen to the audio/podcast hosted on Soundcloud by clicking the Play button below within the browser itself.

Fig. 1: Actual number of doctors versus projected in 2020 and 2030 per population. The black boxes are the doctor:patient ratio.

So you could turn around and say, “but how does this affect me?” I have enough money and resources to see the best doctors in the best clinics and hospitals in this country. As an individual, how is this an adverse “matka” for me?

Let’s look at a few scenarios.

1. Acute care.

If you have a stroke or a heart attack, your outcome depends on how quickly you can get treated. You may be the richest person in Lonavala, or Ranchi or Goa, but if you have a stroke and need to get to a 24/7/365 stroke unit, it would be virtually impossible to do so. More than 90% of hospitals in India can’t handle acute strokes 24/7/365, simply because there isn’t enough manpower (trained interventional neuroradiologists or neurologists), even if we could manage the economics and other infrastructure. And because we are a poor country, we don’t have public services like 911 in the US where paramedics can come and get you quickly or air-lift you in time to the nearest acute stroke care unit. Being moneyed in a poor country does not make it any easier to overcome the challenges of poor public infrastructure.

2. Intensive-care unit outcomes.

Most intensive-care units (ICUs) are supposed to have a patient:nurse ratio of 1:1 [5] for optimal care. This rarely happens in our country, even in the best hospitals, which basically means poorer care and outcomes. We don’t have enough nurses. Period.

3. Covid-19 vaccinations.

The piquant situation is that we may have enough vaccine doses to administer, but we don’t have enough staff to administer these vaccines. And if we pull away staff from other areas to man vaccination centres, then care in those other areas suffers. This is one main reason why, even if you are moneyed, but below the age of 50 and without co-morbidities, you can’t get vaccinated. In the US, as of 19th March, 23.3% of the population has received at least one vaccine dose, while in India it is 2.93% (40 million doses).

4. Sick staff.

If your maid or chauffeur or company workers falls sick, chances are they will need to take a considerable number of days off from work to navigate the public healthcare system including the ESIC, which in turn would adversely affect your personal or your company’s productivity.

5. Preventive care.

There aren’t enough doctors to help you with your preventive care. For example, the vast majority of you, irrespective of the resources you command, will find it hard to find even one doctor willing to spend 30 minutes discussing the pros and cons of statins for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease…forget other issues.

I wrote about Tukaram and the people around him in “The Matka of Better Life Expectancy”, which I published on 17th Jan, 2021. I said “Tukaram and Nathu made it to age 50, but did not make it past age 55. Damodar died at the age of 30 and Phoolbai died in childbirth at age 25. However, if Tukaram and his friends and siblings had been born in the 1960s instead of 1809, all of them would likely be alive today.”

And this is what would have possibly happened to Tukaram.

Tukaram, born in the 1960s in India, would have likely suffered one bout of either malaria or dengue, at least 3-4 influenza episodes, perhaps contracted tuberculosis in his teens or childhood and then in his 50s, with some prosperity, developed type II diabetes and because he started smoking in his teens, at the age of 60, would have landed up with lung cancer. He probably also would have suffered from at least one injury related to riding a scooter or driving a car, probably because he or someone else was not following rules.

Living in India is an adverse matka, irrespective of whether you live on the 35th floor of a tower overlooking the Arabian Sea, or in the mountains of Uttarakhand or on the beach in Pondicherry. Our life expectancy (69.7 years) is lower than those of other countries (84.6 years in Japan) [6] because of the quadruple whammy we live with, irrespective of how rich we are or where we live in India.

The first whammy is of communicable diseases like tuberculosis, malaria and dengue, which are still rampant. The second whammy is of non-communicable diseases like diabetes, hypertension, cancer and cardiovascular diseases, whose incidence is only increasing year by year. The third whammy is of a wholly inadequate health force, which is the focus of this piece and the last is of being poor, either as an individual or as a country or the worst of the worst…being a poor individual in a poor country.

Fig. 2: The adverse health matkas of living in India.

What do we do? If we can’t or don’t migrate to a country with better living conditions and healthcare, then we have to take care of our health ourselves. That is the aim of this newsletter…to understand our adverse matkas and the steps we can take to try and live a longer, healthier life.

The 13-points atmasvasth guide to living long, healthy is a way to help ourselves, to understand what we have to do for a long healthspan and lifespan. We can’t depend on this wholly inadequate system of ours to take care of our health. We have to do it ourselves…because no one else is going to.

Footnotes:

1. Rajya Sabha Unstarred Question Nal 236 of 15th September, 2020.

2. Karan A. Size, composition and distribution of health workforce in India: why, and where to invest. 10.21203/rs.3.rs-102515/v2

3. https://www.nmc.org.in/information-desk/for-students-to-study-in-india/list-of-college-teaching-mbbs

4. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/334226

5. Sharma SK, Rani R. Nurse-to-patient ratio and nurse staffing norms for hospitals in India: A critical analysis of national benchmarks. J Family Med Prim Care. 2020;9(6):2631-2637. Published 2020 Jun 30. doi:10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_248_20

6. https://ourworldindata.org/life-expectancy

Atmasvasth Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.